The patella is the knee cap.

Incidence of Patellar Luxation

Patellar luxation is one of the most common congenital anomalies in dogs. The condition affects primarily small dogs, especially breeds such as Boston terriers, Chihuahuas, Pomeranians, miniature Poodles and Yorkshire Terriers. The incidence in large breed dogs has been on the rise over the past ten years, and breeds such as Chinese Shar pei, flat-coated Retriever, Akita and Great Pyrenees are now considered predisposed to this disease. In our clinical practice we are diagnosing almost as many large breed dogs with patellar luxation as small breed dogs and this includes breeds such as the Labrador, German Shepherd, Newfoundland and Cane Corso. Patellar luxation affects both knees in 50% of all cases, resulting in discomfort and loss of function. Patellar luxation can also affect cats.

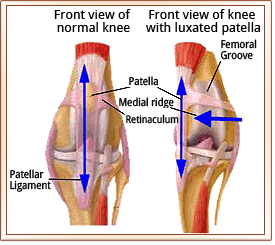

Patellar luxation is usually due to a congenital malformation of the end of the femur (thigh bone) but occasionally results from a traumatic injury to the knee, causing sudden non-weight-bearing lameness of the limb. It may also develop subsequent to cranial cruciate deficiency in dogs that will typically have a chronic history of lameness. The femoral groove into which the knee cap normally rides is commonly shallow or absent in dogs with non-traumatic patellar luxation. Early diagnosis of bilateral disease in the absence of trauma and breed predisposition supports the concept of patellar luxation resulting from a congenital or developmental misalignment of the limb.

- Malformation of the tibia

- Deviation of the tibial crest, the bony prominence onto which the patellar tendon attaches below the knee

- Abnormal conformation of the hip joint, such as hip dysplasia

- Malformation of the femur, with angulation and torsion

- Tightness/atrophy of the quadriceps (thigh) muscles, acting as a bowstring

- A patellar ligament that may be too long

Clinical signs associated with patellar luxation vary greatly with the severity of the disease. The condition may be an incidental finding detected by your veterinarian on a routine physical examination or may cause your pet to carry the affected limb up all the time. Most dogs affected by this disease will suddenly carry the limb up for a few steps, and may be seen shaking or extending the leg prior to regaining its full use. As the disease progresses in duration and severity, this lameness becomes more frequent and eventually becomes continuous. In young puppies with severe medial patellar luxation, the rear legs often present a “bow-legged” appearance that worsens with growth. Large breed dogs with lateral patellar luxation may have a “knocked-in knee” appearance, combining severe lateral patellar luxation and hip dysplasia.

The severity of patellar luxation has been graded on a scale of 0 to 4, based on orthopedic examination of the knee. Surgical treatment is typically considered in grades 2 and over:

| Grade I | Knee cap can be manipulated out of its groove, but returns to its normal position spontaneously |

| Grade II | Knee cap rides out of its groove occasionally and can be replaced in the groove by manipulation |

| Grade III | Knee cap rides out of its groove most of the time but can be replaced in the groove via manipulation |

| Grade IV | Knee cap rides out of its groove all the time and cannot be replaced inside the groove |

Exam, Screening Tests, and Imaging

The diagnosis of patellar luxation is based on palpation of an unstable knee cap on orthopedic examination. Additional tests are often required to diagnose conditions often associated with patellar luxation and help the surgeon recommend the most appropriate treatment for your pet. These may include:

- Palpation of the knee (sometimes under sedation) to assess damage to ligaments

- Radiographs of the pelvis, knee and tibias to evaluate the shape of the bones in the rear leg and rule out hip dysplasia

- Blood work before anesthesia

What Will Happen if Patellar Luxation is Left Untreated?

Every time the knee cap rides out of its groove, cartilage (the normal lining of bones within joints) is damaged, leading to osteoarthritis and associated pain. The knee cap may ride more and more often out of its normal groove, eventually exposing areas of bone. In puppies, the abnormal alignment of the patella may also aggravate the shallowness of the femoral groove and lead to serious deformation of the leg. In all dogs, the abnormal position of the knee cap destabilizes the knee and predisposes affected dogs to rupture their cranial cruciate ligament, at which point they typically stop using the limb.

What Options are Available for Treating Patellar Luxation?

Patellar luxations that do not cause any clinical sign should be monitored but do not typically warrant surgical correction, especially in small dogs. Surgery is considered in grades 2 and over (see above). Surgical treatment of patellar luxation is more difficult in large breed dogs, especially when combined with cranial cruciate disease, hip dysplasia or angulation of the long bones.

One or several of the following strategies may be required to correct patellar luxation:

- Reconstruction of soft tissues surrounding the knee cap to loosen the side toward which the patella is riding and tighten the opposite side.

- Deepening of the femoral groove so that the knee cap can seat deeply in its normal position.

- Moving the tibial crest, the bony prominence onto which the tendon of the patella attaches below the knee. This will help realign the thigh muscles (quadriceps), the patella and its tendon.

- Correction of abnormally shaped femurs is performed rarely but is occasionally required in cases where the knee cap rides outside of its groove most or all the time and there is marked femoral angulation. This procedure involves cutting the bone, correcting its deformation and immobilizing it with a bone plate.

The procedures that will best address the problem are selected on an individual basis by the surgeon that has examined the patient.

The surgeon that has operated on your pet will best be able to advise you and establish a personalized post-operative treatment plan. Exercise is typically limited to leash walks for 6 to 12 weeks depending on the procedures performed and factors affecting the healing capacities of your pet. Radiographs may need to be repeated at regular intervals to monitor bone healing.

Over 90% of owners are satisfied by the progress of their dog after surgery. The prognosis is less favorable in dogs when patellar luxation is combined with other abnormalities, such as angulation of the long bones or hip dysplasia.

Osteoarthritis is expected to progress on radiographs. However, this does not necessarily mean that your dog will suffer or be lame as a result. Keeping your pet slim and encouraging swimming/walking rather than jumping/running will help prevent or minimize clinical signs of osteoarthritis. Oral supplements (Dasuquin- a glucosamine/chondroitin supplement) or a specific diet (Hills J/d diet) may be recommended to promote cartilage function and minimize the progression of osteoarthritis.

Some degree of knee cap instability will persist in up to 50% of cases. This does not cause further lameness in the majority of cases however, a small percentage can have long-term intermittent lameness or develop re-luxation and require additional surgical intervention. Migration or breakage of surgical implants used to maintain bones in position occurs rarely, but can happen, especially if animals are too active too soon after surgery. Occasionally some of the metal implants used can cause discomfit in the post-operative period and if this is the case they can be simply removed once the bone has healed. Infection is a rare complication.

Because it seems likely that this condition could be passed genetically, dogs diagnosed with patellar luxation should not be bred.